The pile cap is a 20-m-thick multi-layered, tiered reinforced concrete top that covers and transfers the load to the foundation barrettes.

Firm footings for tallest tower

In an exclusive interview on the sidelines of the recent Innovative Structural Concrete conference in Dubai, RUBEN FIDALGO DIAS of Besix, outlines the challenges faced in executing the pile cap for Dubai Creek Tower, which is set to be the world’s next tallest tower.

01 January 2019

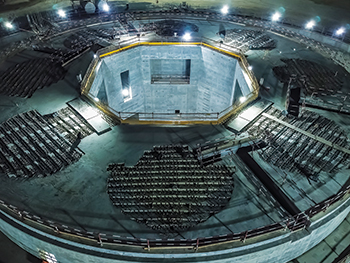

As many as 450 skilled professionals worked day and night to complete the pile cap at Dubai Creek Tower in less than nine months – and two months ahead of schedule. The job involved placing 18,000 tonnes of reinforced steel and pouring 48,000 cu m of concrete.

Dubai Creek Tower’s pile cap is an approximately 20-m-thick multi-layered, tiered reinforced concrete top that covers and transfers the load to the foundation barrettes.

In October 2016, His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of UAE and Ruler of Dubai, marked the ground-breaking of the tower, with the barrettes foundation work, which once completed would make way to execute the pile cap foundations work.

The contract for the pile cap foundation works was awarded to Besix subsidiary, Six Construct. The concrete pouring began in September 2017 and reached over 50 per cent completion in January 2018, with the pile cap having been completed in June 2018.

|

|

Dias ... first pour on the project involved 6,036 cu m of continuous concrete pouring. |

Speaking to OSCAR WENDEL in an exclusive interview for Gulf Construction, Ruben Fidalgo Dias, project manager, Besix, says: “Everyone – and not just the contractor – was fully involved, including Calatrava, Aurecon, DEC, Parsons, Besix and Emaar. That we managed to do it faster than envisioned is a result of every little piece working concurrently. But we were never working with the target to achieve any record.”

He says it was a bit of a step into the unknown. “There were a lot of questions to be answered, because of the sheer volume and the dimension of the project; it’s 20 m high and 70 m in diameter. There were some concerns about how we were going to do it, but once we started, we became more confident.”

The first milestone, Dias says, was to reach the top on the central part of the pile cap. This led to the very first pour on the project being the biggest one – 6,036 cu m of concrete of continuous pouring. “It was our corner stone. With its staggering dimension of 36 m by 36 m and a 5-m height, it allowed to open several fronts and work concurrently on the first contractual milestone while working on the outer part of the pile cap,” he explains.

Dias says they took advantage of the circumstances during the first pour, which had more than 3,200 tonnes of rebar. To build the formwork for this quantity of concrete, a concern for Besix was its uplifting. While pouring concrete, the formwork could rise, and the traditional solution to avoid this is doing a foundation for the formwork itself.

“Our first task was to do blinding so we have a clean environment to work in. Underneath this blinding, you have cathodic protection, cables, trenches for dewatering, and several other things already done by the piling contractor before us.

“One of the things we ended up doing differently was to take advantage of the sheer amount of rebar and tie the formwork to it. Hence, we didn’t have to do the traditional foundation method. This served us well because we eliminated several activities that could have risked damaging other work and were able to do it faster. This was one thing that helped us from the beginning,” Dias points out.

Elaborating further on the formwork aspect, Dias says they divided it to reach the central part after the first pour and then had what they call three ‘rings’, on top of it.

“Initially, it was foreseen to be four concrete ‘rings’. Once we prepared our methods design, we managed to take advantage of bigger formwork panels available in-house. Had we casted one more ring, we would have spent more time because you need to do the concrete curing after casting each ‘ring’. This was also one of the things that helped us reach the top part five weeks ahead of schedule,” Dias explains.

|

|

Dubai Creek Tower ... a rendition. |

Giving details of the pile cap, Dias says there were two contractual milestones. The first was to reach the top of the pile cap (20 m high) on the central part. This would allow the tendering process to proceed and start the building of the tower itself. In parallel, the second and final milestone was to finish the full pile cap surrounding the central part.

“This was our target. The tender drawings had 12 horizontal layers to build the pile cap. This meant we would only reach the top when we finished the pile cap. To achieve the client’s request of achieving the top on the central part first, we proposed dividing the pile cap differently. This led to further rearranging the rebar, further emphasising the original Calatrava’ s design of having three major horizontal zones with rebar,” he says.

As unique as the project is, so was the special concrete mix, developed exclusively for this job, says Dias.

The concrete mix, C70 and C100 – used on the top part of the pile cap – is highly fluid when compared to a standard high-strength concrete. “It’s so fluid it spreads out evenly over the entire area. But it can be a headache too if you don’t have the formwork that is waterproof; the aggregates are a maximum of 10 mm. So they are tiny!”

He says Besix got the LOA (letter of appointment) in March 2017 and concrete testing was started the very next month. Several test trials were done to see what worked. They even did 2 m cubes onsite to measure temperature.

“Since our first pour was in September, we had to study when each pour would take place, if it was going to be placed during winter or summer, and how the temperature differentials would affect it,” says Dias.

|

|

The pile cap was completed in less than nine months. |

Considering the amount of concrete to be poured, he says the possibility of installing some batching plants on site was initially envisioned. From the outset, Unimix was told of the expected rate of delivery per hour of concrete required, which could vary depending on the specific pour, between 150 cu m per hour up to 300 cu m per hour. The company had installed the capacity to supply the required amount. Additionally, there were batching plants in Jebel Ali as well, from where it takes 45 minutes to reach site, and at Al Quoz.

“This meant we could do more than 300 cu m per hour, which we did. The type of concrete – self-compacting – we used also saved time,” adds Dias.

With regard to rebar, Besix had more than 200,000 couplers. Each T40 bar of 12 m is 120 kg, requiring six to eight people to carry it. And they were all connected with couplers.

Dias says deciding on the type of coupler was a challenge since there are so many different alternatives in the market.

He adds: “My first concern was that we would need a coupler that would minimise relocating the bar itself when installing the coupler. The coupler would be first screwed to the rebar, and unscrewed after the rebar was placed. Some couplers, during screwing or unscrewing, require that the bar be moved as well. But this is not practical because of the weight of the rebar.”

Dias further says every gram of concrete and rebar that arrived on site was weighed, adding this is not something that is usually done on every site, but they did it as an additional step of quality control and monitoring strategy.

The concrete trucks arriving on site passed through the weigh bridge, then went to an area where samples were collected from every truck, temperature measured, lab testing done and cylinders taken to crush later on. Thereafter, each truck is designated for a specific pump on site where it goes to distribute concrete as per the requirement there.

“Knowing the amounts of every constituent of the concrete, we knew exactly the weight for each cu m. So instead of counting the number of concrete trucks, we weighed each truck, because the amount of concrete in each truck can vary, even if slightly. Thus, we could monitor the exact quantity arriving on site,” Dias says.

For every pour, there was a pre-pour meeting where targets and requirements were defined and the frequency at which concrete was to be delivered was determined, in addition to the number of pumps, where they were going to be located, the number of trucks coming in and from where, the amount of quantity delivered per hour from each batching plant, etc. “And once everything was planned, we executed it,” says Dias.

The same applied to the rebar. Rebar has a theoretical weight, and when a truck delivered, Besix logged all the data for each delivery.

Dubai Creek Tower, a global icon being built by leading developer Emaar in the heart of the 6-sq-km Dubai Creek Harbour, has been designed by Spanish/Swiss architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava Valls. It will feature several observation decks such as the Pinnacle Room and VIP Observation Garden Decks.

- Firm footings for tallest tower

- ECC makes headway on Nshama projects

- Drake & Scull wins mall contract

- L&T wins top honours at Dubai’s Taqdeer Award