Using architecture to create cooler homes

Passive methods in architectural design can be used to offset the intense impact of solar radiation on buildings and create energy-efficient homes in Bahrain, NOOR ABDULMAGEED* tells Abdulaziz Khattak of Gulf Construction magazine.

01 July 2019

Every region has an identity perceived through social and physical characteristics at a specific time. People and places, however, are exposed to change over time.

In this region’s case, it was the oil discovery in the 1930s that brought about many social, architectural and educational changes – leading to the loss of an architectural identity.

Where we once constructed homes with thick walls using rock from the seabed, we began putting up Western-style structures with materials not suited to our environment. This was compounded by the subsidised energy bills, which meant we discarded our traditional and more sustainable building practices in favour of modern structures that had high energy dependency.

|

|

Abdulmageed ... key study. |

The high ambient temperatures and relative humidity in Bahrain result in high air-conditioning use hence consuming high levels of electricity.

One study on ‘Trends in Residential Energy Consumption’ by Farajallah Alrashed of the School of Engineering and Built Environment at Glasgow Caledonian University, found that 52 per cent of energy was consumed by the region’s residential sector.

Another study on ‘Sustainable Houses in Hot Climates’ conducted in 2014 by Jami Hijazi of University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, demonstrated that air-conditioning accounted for 80 per cent of this consumption.

This has been amplified by global warming, particularly in Bahrain where high summer temperatures, population density and its low elevation mean that climate change mitigation is essential.

Architecture can play a key role in finding solutions to this problem, as evidenced in my study, ‘Reshaping Architectural Choice through Adaptation: Energy efficiency solutions and Renewable opportunities in Bahrain’. This study has proven it is possible to offset the intense impact of solar radiation on buildings by adopting simple strategies.

|

|

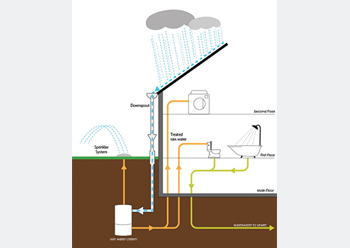

Rain recycling solutions ... partially underground. |

For example, the specific orientation of a structure, shading and the type and amount of glazing can all reduce heat build-up inside.

Another solution is using the earth as a cooling agent by erecting structures partly below ground level, harnessing its colder thermal mass. The temperature underground depends on the depth of excavation.

My investigations, using local weather data and climate analysis, concluded that in this region a proposed depth of five to 10 m would be enough to improve a building’s temperature performance.

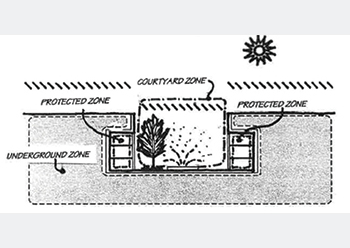

The research included a study of the earth profile in Bahrain, as well as the courtyard effect on an underground level using two prototypes designed and simulated with consideration to orientation, underground water channels, zoning, surface area of contact with earth and thermal data.

It showed heat gains in a free-running house could be reduced by up to 7 deg C using this design, in which homes are partly sheltered by earth.

Bahrain’s urban context is built on a grid, which helps identify optimum locations for such residential units. Maintaining such a grid also helps create wind tunnels for sand storms to pass through and support renewable systems from the design stage or when planning retrofitting solutions.

|

|

Sunken courtyards in the desert climate (study done by Adil A Al-mumin). |

Meanwhile, spaces with higher internal heat gains – such as kitchens or laundry rooms – can be located strategically within the home at locations closest to the earth barrier.

With the addition of appropriate ventilation, months in which mechanical cooling is used can be reduced by, at least, half using this design method.

However, it is important to use materials that have a high thermal mass and strength to handle the pressure of earth sheltering.

The ground temperature profile at a depth of seven to 10 m is a constant 22 deg C, with Bahrain’s rich fabric of underground water channels contributing to the cooler environment.

However, other strategies can also be adopted, such as adding louvres, meshes and top shadings to further reduce the structure’s exposure to heat.

Courtyards are also very effective, especially if they contain water bodies and vegetation – and are also built below ground level.

In addition, jacket facades can be used to provide an extra layer of protection for the structure, while creating a microclimate in the middle space. This helps reduce the building’s exposure to direct radiation and improves privacy.

In fact, jacket facades can be a massive factor in regulating heat balance, creating a buffer zone.

Vegetation can be introduced to enhance air quality indoors and outdoors.

However, a decisive factor in minimising exposure to the sun is the orientation of the structure and minimum glazing on the south facade reduces heat penetration further. Sustainability can be further enhanced through the use of solar glazing.

The prototypes, designed and tested, have been developed based on scientific and environmental evaluation, but with also a social consideration.

Many people are unaware of the benefits of such building strategies, which means more education and awareness is required, as is a change in perceptions of a community that is used to subsidised, cheap resources.

However, such strategies must also take into account social norms, such as the need to preserve the privacy of homes.

A survey of approximately 150 people found that privacy was essential for the respondents, who were completely dependent on mechanical cooling and lacked knowledge on environmental techniques.

The findings also suggested that the respondents were open to new ideas to reduce their reliance on air-conditioning, particularly at a time when electricity subsidies are being removed.

* Noorihan Abdulmageed is senior designer and architect specialised in sustainable solutions at Steer and Sterling. She holds a Bachelors in Architecture from King Faisal University and a Masters in Architecture and Environmental Design from the University of Westminster.

- Using architecture to create cooler homes

- Panasonic eco-friendly air-conditioners unveiled

- Galloway geared to boost indoor air quality

- Greenheck expands ventilation line

- Ziehl-Abegg fans win FEI certification